Rabbit

| Rabbit | |

|---|---|

| |

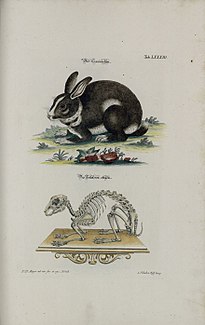

| European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Lagomorpha |

| Family: | Leporidae |

| Included genera | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

Rabbits are small rodent mammals in the family Leporidae (which also includes the hares), which is in the order Lagomorpha (which also includes pikas). They are familiar throughout the world as a wild prey animal, a domesticated form of livestock, and a pet, having a widespread effect on ecologies and cultures. The most widespread rabbit genera are Oryctolagus and Sylvilagus. The former, Oryctolagus, includes the European rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus, which is the ancestor of the hundreds of breeds of domestic rabbit and has been introduced on every continent except Antarctica. The latter, Sylvilagus, includes over 13 wild rabbit species, among them the cottontails and tapetis. Wild rabbits not included in Oryctolagus and Sylvilagus include several species of limited distribution, including the pygmy rabbit, volcano rabbit, and Sumatran striped rabbit.

Rabbits are a paraphyletic grouping, and do not constitute a clade, as hares (belonging to the genus Lepus) are nested within the Leporidae clade and are not described as rabbits. Although once considered rodents, lagomorphs diverged earlier and have a number of traits rodents lack, including two extra incisors. Similarities between rabbits and rodents were once attributed to convergent evolution, but studies in molecular biology have found a common ancestor between lagomorphs and rodents and place them in the clade Glires.

Rabbit physiology is suited to escaping predators and surviving in various habitats, living either alone or in groups in nests or burrows. As prey animals, rabbits are constantly aware of their surroundings, having a wide field of vision and ears with high surface area to detect potential predators. The ears of a rabbit are essential for thermoregulation and contain a high density of blood vessels. The bone structure of a rabbit's hind legs, which is longer than that of the fore legs, allows for quick hopping, which is beneficial for escaping predators and can provide powerful kicks if captured. Rabbits are typically nocturnal and often sleep with their eyes open. They reproduce quickly, having short pregnancies, large litters of four to twelve kits, and no particular mating season; however, the mortality rate of rabbit embryos is high, and there exist several widespread diseases that affect rabbits, such as rabbit hemorrhagic disease and myxomatosis. In some regions, especially Australia, rabbits have caused ecological problems and are regarded as a pest.

Humans have used rabbits as livestock since at least the first century BC in ancient Rome, raising them for their meat, fur and wool. The various breeds of the European rabbit have been developed to suit each of these products; the practice of raising and breeding rabbits as livestock is known as cuniculture. Rabbits are seen in human culture globally, appearing as a symbol of fertility, cunning, and innocence in major religions, historical and contemporary art.

Terminology and etymology

The word rabbit derives from the Middle English rabet ("young of the coney"), a borrowing from the Walloon robète, which was a diminutive of the French or Middle Dutch robbe ("rabbit"), a term of unknown origin.[1] The term coney is a term for an adult rabbit used until the 18th century; rabbit once referred only to the young animals.[2] More recently, the term kit or kitten has been used to refer to a young rabbit.[3][4] The endearing word bunny is attested by the 1680s as a diminutive of bun, a term used in Scotland to refer to rabbits and squirrels.[5]

Coney is derived from cuniculus,[2] a Latin term referring to rabbits which has been in use from at least the first century BCE in Hispania. The word cuniculus may originate from a diminutive form of the word for "dog" in the Celtic languages.[6]

A group of rabbits is known as a colony,[7] nest, or warren,[8] though the latter term more commonly refers to where the rabbits live.[9] A group of baby rabbits produced from a single mating is referred to as a litter[10] and a group of domestic rabbits living together is sometimes called a herd.[8]

A male rabbit is called a buck, as are male goats and deer, derived from the Old English bucca or bucc, meaning "he-goat" or "male deer", respectively.[11] A female is called a doe, derived from the Old English dā, related to dēon ("to suck").[12]

Taxonomy and evolution

Rabbits and hares were formerly classified in the order Rodentia (rodents) until 1912, when they were moved into the order Lagomorpha (which also includes pikas). Since 1945, there has been support for the clade Glires that includes both rodents and lagomorphs,[13] though the two groups have always been closely associated in taxonomy; fossil,[14] DNA,[15] and retrotransposon[16] studies in the 2000s have solidified support for the clade. Studies in paleontology and molecular biology suggest that rodents and lagomorphs diverged at the start of the Tertiary period.[17]

|

The extant species of family Leporidae, of which there are more than 70, are contained within 11 genera, one of which is Lepus, the hares. There are 32 extant species within Lepus. The cladogram is from Matthee et al., 2004, based on nuclear and mitochondrial gene analysis.[18]

Classification

- Order Lagomorpha

- Genus Brachylagus

- Pygmy rabbit, Brachylagus idahoensis

- Genus Bunolagus

- Riverine rabbit, Bunolagus monticularis

- Genus Caprolagus

- Hispid hare, Caprolagus hispidus

- Genus Lepus[a]

- Genus Nesolagus

- Sumatran striped rabbit, Nesolagus netscheri

- Annamite striped rabbit, Nesolagus timminsi

- Genus Oryctolagus

- European rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus

- Genus Pentalagus

- Amami rabbit/Ryūkyū rabbit, Pentalagus furnessi

- Genus Poelagus

- Bunyoro rabbit, Poelagus marjorita

- Genus Pronolagus

- Natal red rock hare, Pronolagus crassicaudatus

- Jameson's red rock hare, Pronolagus randensis

- Smith's red rock hare, Pronolagus rupestris

- Hewitt's red rock hare, Pronolagus saundersiae

- Genus Romerolagus

- Volcano rabbit, Romerolagus diazi

- Genus Sylvilagus

- Andean tapeti, Sylvilagus andinus

- Bogota tapeti, Sylvilagus apollinaris

- Swamp rabbit, Sylvilagus aquaticus

- Desert cottontail, Sylvilagus audubonii

- Brush rabbit, Sylvilagus bachmani

- Common tapeti, Sylvilagus brasiliensis

- Mexican cottontail, Sylvilagus cunicularis

- Ecuadorian tapeti, Sylvilagus daulensis

- Dice's cottontail, Sylvilagus dicei

- Eastern cottontail, Sylvilagus floridanus

- Fulvous tapeti, Sylvilagus fulvescens

- Central American tapeti, Sylvilagus gabbi

- Tres Marias cottontail, Sylvilagus graysoni

- Robust cottontail, Sylvilagus holzneri

- Northern tapeti, Sylvilagus incitatus

- Omilteme cottontail, Sylvilagus insonus

- Nicefor's tapeti, Sylvilagus nicefori

- Mountain cottontail, Sylvilagus nuttallii

- Appalachian cottontail, Sylvilagus obscurus

- Marsh rabbit, Sylvilagus palustris

- Suriname tapeti, Sylvilagus parentum

- Colombian tapeti, Sylvilagus salentus

- Santa Marta tapeti, Sylvilagus sanctaemartae

- Western tapeti, Sylvilagus surdaster

- Coastal tapeti, Sylvilagus tapetillus

- New England cottontail, Sylvilagus transitionalis

- Venezuelan lowland rabbit, Sylvilagus varynaensis

Differences from hares

The term rabbit is typically used for all Leporidae species, excluding the genus Lepus. Members of that genus are known as hares[20] or jackrabbits.[21]

Lepus species are precocial, born relatively mature and mobile with hair and good vision out in the open air, while rabbit species are altricial, born hairless and blind in burrows and buried nests.[22] Hares are also generally larger than rabbits, and have longer pregnancies.[20] Hares and some rabbits live relatively solitary lives above the ground in open grassy areas,[23] interacting mainly during breeding season.[24][25] Some rabbit species group together to reduce their chance of being preyed upon,[26] and the European rabbit will form large social groups in burrows,[27] which are grouped together to form warrens.[28][29] Burrowing by hares varies by location, and is more prominent in younger members of the genus;[24] many rabbit species that do not dig their own burrows will use the burrows of other animals.[30][31]

Rabbits and hares have historically not occupied the same locations, and only became sympatric relatively recently; historic accounts describe antagonistic relationships between rabbits and hares, specifically between the European hare and European or cottontail rabbits, but scientific literature since 1956 has found no evidence of aggression or undue competition between rabbits and hares. When they appear in the same habitat, rabbits and hares can co-exist on similar diets.[32] Hares will notably force other hare species out of an area to control resources, but are not territorial.[33] When faced with predators, hares will escape by outrunning them, whereas rabbits, being smaller and less able to reach the high speeds of longer-legged hares, will try to seek cover.[26]

Descendants of the European rabbit are commonly bred as livestock and kept as pets, whereas no hares have been domesticated, though populations have been introduced to non-native habitats for use as a food source.[23] The breed known as the Belgian hare is actually a domestic rabbit which has been selectively bred to resemble a hare,[34] most likely from Flemish Giant stock originally.[35] Common names of hare and rabbit species may also be confused; "jackrabbits" refer to hares, and the hispid hare is a rabbit.[36]

Domestication

Rabbits, specifically the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) species, have long been domesticated. The European rabbit has been widely kept as livestock, starting in ancient Rome from at least the first century BC. Selective breeding, which began in the Middle Ages, has generated a wide variety of rabbit breeds, of which many (since the early 19th century) are also kept as pets.[37] Some strains of European rabbit have been bred specifically as research subjects, such as the New Zealand white.[38]

As livestock, European rabbits are bred for their meat and fur. The earliest breeds were important sources of meat,[39][40] and so were bred to be larger than wild rabbits at younger ages,[41] but domestic rabbits in modern times range in size from dwarf to giant.[42][43] Rabbit fur, produced as a byproduct of meat production but occasionally selected for as in the case of the Rex rabbit,[44] can be found in a broad range of coat colors and patterns, some of which are produced via dyeing.[45] Some breeds are raised for their wool, such as the Angora rabbit breeds;[46] their fur is sheared, combed or plucked, and the fibers are spun into yarn.[47]

Biology

Evolution

The earliest ancestor of rabbits and hares lived 55 million years ago in what is now Mongolia.[48] Because the rabbit's epiglottis is engaged over the soft palate except when swallowing, the rabbit is an obligate nasal breather.[49] As lagomorphs, rabbits have two sets of incisor teeth, one behind the other, a manner in which they differ from rodents, which only have one set of incisors.[20] Another difference is that for rabbits, all of their teeth continue to grow, whereas for most rodents, only their incisors continue to grow. Carl Linnaeus originally grouped rabbits and rodents under the class Glires; later, they were separated as the scientific consensus is that many of their similarities were a result of convergent evolution. DNA analysis and the discovery of a common ancestor have supported the view that they share a common lineage, so rabbits and rodents are now often grouped together in the clade or superorder Glires.[50][16]

Morphology

Since speed and agility are a rabbit's main defenses against predators, rabbits have large hind leg bones and well-developed musculature. Though plantigrade at rest, rabbits are on their toes while running, assuming a more digitigrade posture.[51] Rabbits use their strong claws for digging and (along with their teeth) for defense.[52] Each front foot has four toes plus a dewclaw. Each hind foot has four toes (but no dewclaw).[53]

Most wild rabbits (especially compared to hares) have relatively full, egg-shaped bodies. The soft coat of the wild rabbit is agouti in coloration (or, rarely, melanistic), which aids in camouflage. The tail of the rabbit (with the exception of the cottontail species) is dark on top and white below. Cottontails have white on the top of their tails.[54]

As a result of the position of the eyes in its skull and the size of the cornea, the rabbit has a panoramic field of vision that encompasses nearly 360 degrees.[55] However, there is a blind spot at the bridge of the nose, and because of this, rabbits cannot see what is below their mouth and rely on their lips and whiskers to determine what they are eating. Blinking occurs 2 to 4 times an hour.[50]

Hind limb elements

The anatomy of rabbits' hind limbs is structurally similar to that of other land mammals and contributes to their specialized form of locomotion. The bones of the hind limbs consist of long bones (the femur, tibia, fibula, and phalanges) as well as short bones (the tarsals). These bones are created through endochondral ossification during fetal development. Like most land mammals, the round head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum of the os coxae, the hip bone. The femur articulates with the tibia, but not the fibula, which is fused to the tibia. The tibia and fibula articulate with the tarsals of the pes, commonly called the foot. The hind limbs of the rabbit are longer than the front limbs. This allows them to produce their hopping form of locomotion. Longer hind limbs are more capable of producing faster speeds. Hares, which have longer legs than cottontail rabbits, are able to move considerably faster.[56] The hind feet have four long toes that allow for digitigrade movement, which are webbed to prevent them from spreading when hopping.[57] Rabbits do not have paw pads on their feet like most other animals that use digitigrade locomotion. Instead, they have coarse compressed hair that offers protection.[58]

Musculature

Rabbits have muscled hind legs that allow for maximum force, maneuverability, and acceleration that is divided into three main parts: foot, thigh, and leg. The hind limbs of a rabbit are an exaggerated feature. They are much longer and can provide more force than the forelimbs,[59] which are structured like brakes to take the brunt of the landing after a leap.[60] The force put out by the hind limbs is contributed by both the structural anatomy of the fusion of the tibia and fibula, and by the muscular features.[59]

Bone formation and removal, from a cellular standpoint, is directly correlated to hind limb muscles. Action pressure from muscles creates force that is then distributed through the skeletal structures. Rabbits that generate less force, putting less stress on bones are more prone to osteoporosis due to bone rarefaction.[61] In rabbits, the more fibers in a muscle, the more resistant to fatigue. For example, hares have a greater resistance to fatigue than cottontails. The muscles of rabbit's hind limbs can be classified into four main categories: hamstrings, quadriceps, dorsiflexors, or plantar flexors. The quadriceps muscles are in charge of force production when jumping. Complementing these muscles are the hamstrings, which aid in short bursts of action. These muscles play off of one another in the same way as the plantar flexors and dorsiflexors, contributing to the generation and actions associated with force.[62]

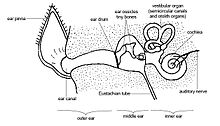

Ears

Within the order of lagomorphs, the ears are used to detect and avoid predators.[63] In the family Leporidae, the ears are typically longer than they are wide, and are in general relatively long compared to other mammals.[25][64]

According to Allen's rule, endothermic animals adapted to colder climates have shorter, thicker limbs and appendages than those of similar animals adapted to warm climates. The rule was originally derived by comparing the ear lengths of Lepus species across the various climates of North America.[65] Subsequent studies show that this rule remains true in the Leporidae for the ears specifically,[66] in that the surface area of rabbits' and hares' ears are enlarged in warm climates;[67] the ears are an important structure to aid thermoregulation[68] as well as in detecting predators due to the way the outer, middle, and inner ear muscles coordinate with one another. The ear muscles also aid in maintaining balance and movement when fleeing predators.[69]

The auricle, also known as the pinna, is a rabbit's outer ear.[70] The rabbit's pinnae represent a fair part of the body surface area. It is theorized that the ears aid in dispersion of heat at temperatures above 30 °C (86 °F), with rabbits in warmer climates having longer pinnae due to this. Another theory is that the ears function as shock absorbers that could aid and stabilize rabbits' vision when fleeing predators, but this has typically only been seen in hares.[50] The rest of the outer ear has bent canals that lead to the eardrum or tympanic membrane.[71]

The middle ear, separated by the outer eardrum in the back of the rabbit's skull, contains three bones: the hammer, anvil, and stirrup, collectively called ossicles, which act to decrease sound before it hits the inner ear; in general, the ossicles act as a barrier to the inner ear for sound energy.[71]

Inner ear fluid, called endolymph, receives the sound energy. After receiving the energy. The inner ear comprises two parts: the cochlea that uses sound waves from the ossicles, and the vestibular apparatus that manages the rabbit's position in regard to movement. Within the cochlea a basilar membrane contains sensory hair structures that send nerve signals to the brain, allowing it to recognize different sound frequencies. Within the vestibular apparatus three semicircular canals help detect angular motion.[71]

Thermoregulation

The pinnae, which contain a vascular network and arteriovenous shunts, aid in thermoregulation.[50] In a rabbit, the optimal body temperature is around 38.5–40.0 °C (101.3–104.0 °F).[73] If their body temperature exceeds or does not meet this optimal temperature, the rabbit must make efforts to return to homeostasis. Homeostasis of body temperature is maintained by changing the amount of blood flow that passes through the highly vascularized ears,[68][74] as rabbits have few to no sweat glands.[75] Rabbits may also regulate their temperature by resting in depressions in the ground, known as forms.[76]

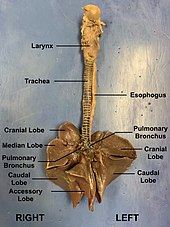

Respiratory system

The rabbit's nasal cavity lies dorsal to the oral cavity, and the two compartments are separated by the hard and soft palate.[77] The nasal cavity itself is separated into a left and right side by a cartilage barrier, and it is covered in fine hairs that trap dust before it can enter the respiratory tract.[77][78] As the rabbit breathes, air flows in through the nostrils along the alar folds. From there, the air moves into the nasal cavity, also known as the nasopharynx, down through the trachea, through the larynx, and into the lungs.[79][80] The larynx functions as the rabbit's voice box, which enables it to produce a wide variety of sounds.[78] The trachea is a long tube embedded with cartilaginous rings that prevent the tube from collapsing as air moves in and out of the lungs. The trachea then splits into a left and right bronchus, which meet the lungs at a structure called the hilum. From there, the bronchi split into progressively more narrow and numerous branches. The bronchi branch into bronchioles, into respiratory bronchioles, and ultimately terminate at the alveolar ducts. The branching that is typically found in rabbit lungs is a clear example of monopodial branching, in which smaller branches divide out laterally from a larger central branch.[81]

The structure of the rabbit's nasal and oral cavities necessitates breathing through the nose. This is due to the fact that the epiglottis is fixed to the backmost portion of the soft palate.[80] Within the oral cavity, a layer of tissue sits over the opening of the glottis, which blocks airflow from the oral cavity to the trachea.[77] The epiglottis functions to prevent the rabbit from aspirating on its food. Further, the presence of a soft and hard palate allow the rabbit to breathe through its nose while it feeds.[79]

Rabbits' lungs are divided into four lobes: the cranial, middle, caudal, and accessory lobes. The right lung is made up of all four lobes, while the left lung only has two: the cranial and caudal lobes.[81] To provide space for the heart, the left cranial lobe of the lungs is significantly smaller than that of the right.[77] The diaphragm is a muscular structure that lies caudal to the lungs and contracts to facilitate respiration.[77][80]

Diet and digestion

Rabbits are strict herbivores[26][36] and are suited to a diet high in fiber, mostly in the form of cellulose. They will typically graze grass upon waking up and emerging from a burrow, and will move on to consume vegetation and other plants throughout the waking period; rabbits have been known to eat a wide variety of plants, including tree leaves and fruits, though consumption of fruit and lower fiber foods is common for pet rabbits where natural vegetation is scarce.[82]

Easily digestible food is processed in the gastrointestinal tract and expelled as regular feces. To get nutrients out of hard to digest fiber, rabbits ferment fiber in the cecum (part of the gastrointestinal tract) and then expel the contents as cecotropes, which are reingested (cecotrophy). The cecotropes are then absorbed in the small intestine to use the nutrients.[83] Soft cecotropes are usually consumed during periods of rest in underground burrows.[82]

Rabbits cannot vomit;[84] and therefore if buildup occurs within the intestines (due often to a diet with insufficient fibre),[85] intestinal blockage can occur.[86]

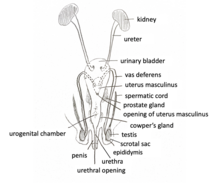

Reproduction

The adult male reproductive system forms the same as most mammals with the seminiferous tubular compartment containing the Sertoli cells and an adluminal compartment that contains the Leydig cells.[87] The Leydig cells produce testosterone, which maintains libido[87] and creates secondary sex characteristics such as the genital tubercle and penis. The Sertoli cells triggers the production of Anti-Müllerian duct hormone, which absorbs the Müllerian duct. In an adult male rabbit, the sheath of the penis is cylinder-like and can be extruded as early as two months of age.[88] The scrotal sacs lay lateral to the penis and contain epididymal fat pads which protect the testes. Between 10 and 14 weeks, the testes descend and are able to retract into the pelvic cavity to thermoregulate.[88] Furthermore, the secondary sex characteristics, such as the testes, are complex and secrete many compounds. These compounds include fructose, citric acid, minerals, and a uniquely high amount of catalase,[87] all of which affect the characteristics of rabbit semen; for instance, citric acid is positively correlated with agglutination,[89] and high amounts of catalase protect against premature capacitation.[90]

The adult female reproductive tract is bipartite, which prevents an embryo from translocating between uteri.[91] The female urethra and vagina open into a urogenital sinus with a single urogenital opening.[92] The two uterine horns communicate to two cervixes and forms one vaginal canal. Along with being bipartite, the female rabbit does not go through an estrus cycle, which causes mating induced ovulation.[88]

The average female rabbit becomes sexually mature at three to eight months of age and can conceive at any time of the year for the duration of her life. Egg and sperm production can begin to decline after three years,[87] with some species such as those in genus Oryctolagus completely stopping reproduction at 6 years of age.[93] During mating, the male rabbit will insert his penis into the female from behind, make rapid pelvic thrusts until ejaculation, and throw himself backward off the female. Copulation lasts only 20–40 seconds.[94]

The rabbit gestation period is short and ranges from 27 to 30 days.[26] A longer gestation period will generally yield a smaller litter while shorter gestation periods will give birth to a larger litter. The size of a single litter can range from 1 to 12 kits, depending on species.[95] After birth, the only role of males is to protect the young from other rabbits, and the mother will leave the young in the nest most of the day, returning to nurse them once every 24 hours.[26] The female can become pregnant again as early as the next day.[88]

After mating, the doe will begin to dig a burrow or prepare a nest before giving birth. Between three days and a few hours before giving birth another series of hormonal changes will cause her to prepare the nest structure. The doe will first gather grass for a structure, and an elevation in prolactin shortly before birth will cause her fur to shed that the doe will then use to line the nest, providing insulation for the newborn kits.[96]

The mortality rates of embryos are high in rabbits and can be due to infection, trauma, poor nutrition and environmental stress. A high fertility rate is necessary to counter this.[88] More than half of rabbit pregnancies are aborted, causing embryos to be resorbed into the mother's body;[93] vitamin deficiencies are a major cause of abortions in domestic rabbits.[97]

Sleep

Rabbits may appear to be crepuscular, but many species[26] are naturally inclined towards nocturnal activity.[98] In 2011, the average sleep time of a rabbit in captivity was calculated at 8.4 hours per day;[99] previous studies have estimated sleep periods as long as 11.4 hours on average, undergoing both slow-wave and rapid eye movement sleep.[100][101] Newborn rabbits will sleep for 22 hours a day before leaving the nest.[102] As with other prey animals, rabbits often sleep with their eyes open, so that sudden movements will awaken the rabbit to respond to potential danger.[103]

Diseases and immunity

In addition to being at risk of disease from common pathogens such as Bordetella bronchiseptica and Escherichia coli, rabbits can contract the virulent, species-specific viruses myxomatosis,[104] and a form of calicivirus which causes rabbit hemorrhagic disease.[105] Myxomatosis is more hazardous to pet rabbits, as wild rabbits often have some immunity.[106] Among the parasites that infect rabbits are tapeworms (such as Taenia serialis), external parasites (including fleas and mites), coccidia species, Encephalitozoon cuniculi,[107] and Toxoplasma gondii.[108][109] Domesticated rabbits with a diet lacking in high-fiber sources, such as hay and grass, are susceptible to potentially lethal gastrointestinal stasis.[110] Rabbits and hares are almost never found to be infected with rabies and have not been known to transmit rabies to humans.[111]

Rabbit hemorrhagic disease (RHD) is a highly infectious rabbit-specific disease caused by strains of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV), including type 2 (RHDV2).[112] The disease was first described in domestic Angora rabbits imported from Germany to Jiangsu, China in 1984, and quickly spread to Korea, Italy, and the rest of Europe. The disease spread to the Americas from 1988, first appearing in rabbits imported to Mexico, but subsequent outbreaks were infrequent, as RHDV only affected the European rabbit species.[113] RHDV2, a strain of RHD-causing virus that affects both domestic and wild lagomorphs, such as hares, was detected for the first time in France in 2010.[114] RHDV2 has since spread to the rest of Europe, Canada,[115] Australia,[116] and the United States.[117][112]

Ecology

Rabbits are prey animals. In Mediterranean Europe, for example, rabbits are the main prey of red foxes, badgers, and Iberian lynxes.[118] To avoid predation and to navigate underground, rabbits have heightened senses (compared to humans) and are constantly aware of their surroundings. If confronted by a potential threat, a rabbit may freeze and observe, then warn others in the warren with powerful thumps on the ground from a hind foot. Rabbits have a remarkably wide field of vision, and a good deal of it is devoted to overhead scanning.[119] A rabbit eye has no fovea, but a "visual streak", a horizontal line in the middle of the retina where both rod and cone cell densities are the highest. This allows them to scan the horizon with little head turning.[120][121]

Rabbits survive predation by burrowing (in some species),[122] and hopping away[60] to dense cover.[26] Their strong teeth allow them to bite to escape a struggle.[123]

The longest-lived rabbit on record, a domesticated European rabbit living in Tasmania, died at age 18.[124] The lifespan of wild rabbits is much shorter; the average longevity of an eastern cottontail, for instance, is about one[125] to five years.[126] The various species of rabbit have been recorded as living from four[127][128] to 13 years in captivity.[129][130]

Habitat and range

Rabbit habitats include forests, steppes, plateaus, deserts,[131] and swamps.[132] Some species, such as the volcano rabbit (Romerolagus diazi) have especially limited distribution due to their habitat needs.[133] Rabbits live in groups, or colonies, varying in behavior depending on species and often using the burrows of other animals or creating nests in holes.[122] The European rabbit notably lives in extensive burrow networks called warrens.[134]

Rabbits are native to North America, southwestern Europe, Southeast Asia, Sumatra, some islands of Japan, and parts of Africa and South America. They are not naturally found in most of Eurasia, where a number of species of hares are present.[135] A 2003 study on domestic rabbits in China found that "(so-called) Chinese rabbits were introduced from Europe", and that "genetic diversity in Chinese rabbits was very low".[136]

Rabbits first entered South America relatively recently, as part of the Great American Interchange.[135] Much of the continent was considered to have just one species of rabbit, the tapeti,[137][b] and most of South America's Southern Cone has had no rabbits until the introduction of the European rabbit, which has been introduced to many places around the world,[54] in the late 19th century.[138]

Rabbits have been launched into space orbit.[139]

Marking

Both sexes of rabbits often rub their chins on objects with their scent gland located under the chin. This is the rabbit's way of marking their territory or possessions for other rabbits to recognize by depositing scent gland secretions. Rabbits who have bonded will respect each other's smell, which indicates a territorial border.[140] Rabbits also have scent glands that produce a strong-smelling waxy substance near their anuses.[141] Territorial marking by scent glands has been documented among both domestic[142] and wild rabbit species.[26]

Environmental problems

Rabbits, particularly the European rabbit,[26] have been a source of environmental problems when introduced into the wild by humans. As a result of their appetites, and the rate at which they breed, feral rabbit depredation can be problematic for agriculture. Gassing (fumigation of warrens),[143] barriers (fences),[144] shooting, snaring, and ferreting[145][146] have been used to control rabbit populations,[147] but the most effective measures are diseases such as myxomatosis and calicivirus.[148] In Europe, where domestic rabbits are farmed on a large scale, they can be protected against myxomatosis and calicivirus via vaccination.[149] Rabbits in Australia and New Zealand are considered to be such a pest that landowners are legally obliged to control them.[150][151]

Rabbits are known to be able to catch fire and spread wildfires, but the efficiency and relevance of this method has been doubted by forest experts who contend that a rabbit on fire could move some meters.[152][153] Knowledge on fire-spreading rabbits is based on anecdotes as there is no known scientific investigation on the subject.[153]

As food and clothing

Humans have hunted rabbits for food since at least the onset of the Last Glacial Maximum,[154] and wild rabbits and hares are still hunted for their meat as game.[155] Hunting is accomplished with the aid of trained falcons,[156] ferrets,[157] or dogs (a common hunting breed being beagles),[158] as well as with snares,[159] rifles and other guns.[158] A caught rabbit may be dispatched with a sharp blow to the back of its head, a practice from which the term rabbit punch is derived.[1][160]

Wild leporids comprise a small portion of global rabbit-meat consumption. Domesticated descendants of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) that are bred and kept as livestock (a practice called cuniculture) account for the estimated 200 million tons of rabbit meat produced annually.[161] Approximately 1.2 billion rabbits are slaughtered each year for meat worldwide.[162] In 1994, the countries with the highest consumption per capita of rabbit meat were Malta with 8.89 kg (19.6 lb), Italy with 5.71 kg (12.6 lb), and Cyprus with 4.37 kg (9.6 lb). The largest producers of rabbit meat were China, Russia, Italy (specifically Veneto[104]), France, and Spain.[163] Rabbit meat was once a common commodity in Sydney, with European rabbits having been introduced intentionally to Australia for hunting purposes,[164] but declined after the myxomatosis virus was intentionally introduced to control the exploding population of feral rabbits in the area.[165]

In the United Kingdom, fresh rabbits are sold in butcher shops and markets, and some supermarkets sell frozen rabbit meat. It is sold in farmers markets there, including the Borough Market in London.[166] Rabbit meat is a feature of Moroccan cuisine, where it is cooked in a tajine with "raisins and grilled almonds added a few minutes before serving".[167] In China, rabbit meat is particularly popular in Sichuan cuisine, with its stewed rabbit, spicy diced rabbit, BBQ-style rabbit, and even spicy rabbit heads, which have been compared to spicy duck neck.[161] In the United States, rabbits sold as food are typically the domestic New Zealand, Belgian, and Chinese rabbits, or Scottish hares.[168]

An infectious disease associated with rabbits-as-food is tularemia (also known as rabbit fever), which may be contracted from an infected rabbit.[169] The disease can cause symptoms of fever, skin ulcers and enlarged lymph nodes, and can occasionally lead to pneumonia or throat infection.[170] Secondary vectors of tularemia include tick and fly bites, which may be present in the fur of a caught rabbit.[169] Inhaling the bacteria during the skinning process increases the risk of getting tularemia;[171] preventative measures against this include the use of gloves and face masks. Prior to the development of antibiotics, such as docycycline and gentamicin, the death rate associated with tularemia infections was 60%, which has since decreased to less than 4%.[172]

In addition to their meat, domestic rabbits are used for their wool[47] and fur for clothing,[173] as well as their nitrogen-rich manure and their high-protein milk.[174] Production industries have developed domesticated rabbit breeds (such as the Angora rabbit) for the purpose of meeting these needs.[44] In 1986, the number of rabbit skins produced annually in France was as high as 70 million, compared to 25 million mink pelts produced at the same time. However, rabbit fur is on the whole a byproduct of rabbit meat production, whereas minks are bred primarily for fur production.[175]

In culture

Rabbits are often posited by scholars as symbols of fertility,[176] sexuality and spring, though they have been variously interpreted throughout history.[177] Up until the end of the 18th century, it was widely believed that rabbits and hares were hermaphrodites, contributing to a possible view of rabbits as "sexually aberrant".[178] The Easter Bunny is a figure from German folklore that then spread to America and later other parts of the world and is similar to Santa Claus, albeit both with softened roles compared to earlier incarnations of the figures.[179]

The rabbits' role as a prey animal with few defenses evokes vulnerability and innocence in folklore and modern children's stories, and rabbits appear as sympathetic characters, able to connect easily with youth, though this particular symbolic depiction only became popular in the 1930s following the massive popularization of the pet rabbit decades before.[176] Additionally, they have not been limited to sympathetic depictions since then, as in literature such as Watership Down[180][181] and the works of Ariel Dorfman.[182] With its reputation as a prolific breeder, the rabbit juxtaposes sexuality with innocence, as in the Playboy Bunny.[183] The rabbit has also been used as a symbol of playfulness and endurance, as represented by the Energizer Bunny and the Duracell Bunny.[184]

Folklore and mythology

The rabbit often appears in folklore as the trickster archetype, as he uses his cunning to outwit his enemies. In Central Africa, the common hare (Kalulu) is described as a trickster figure,[185] and in Aztec mythology, a pantheon of four hundred rabbit gods known as Centzon Totochtin, led by Ometochtli or Two Rabbit, represented fertility, parties, and drunkenness.[186] Rabbits in the Americas varied in mythological symbolism: in Aztec mythology, they were also associated with the moon,[186] and in Anishinaabe traditional beliefs, held by the Ojibwe and some other Native American peoples, Nanabozho, or Great Rabbit,[187] is an important deity related to the creation of the world.[188] More broadly, a rabbit's foot may be carried as an amulet, believed to bring protection and good luck. This belief is found in many parts of the world, with the earliest use being recorded in Europe c. 600 BC.[189]

Rabbits also appear in Chinese, Vietnamese, Japanese and Korean mythology, though rabbits are a relatively new introduction to some of these regions. In Chinese folklore, rabbits accompany Chang'e on the Moon,[190] and the moon rabbit is a prominent symbol in the Mid-Autumn Festival.[191] In the Chinese New Year, the zodiacal rabbit or hare is one of the twelve celestial animals in the Chinese zodiac.[192] At the time of the zodiacal cycles becoming associated with animals in the Han dynasty,[193] only hares were native to China, with the currently extant breeds of rabbit in China being of European origin.[136] The Vietnamese zodiac includes a zodiacal cat in place of the rabbit. The most common explanation is that the ancient Vietnamese word for "rabbit" (mao) sounds like the Chinese word for "cat" (卯, mao).[194] In Japanese tradition, rabbits live on the Moon where they make mochi.[195] This comes from interpreting the pattern of dark patches on the moon as a rabbit standing on tiptoes on the left pounding on an usu, a Japanese mortar.[196] In Korean mythology, as in Japanese, rabbits live on the moon making rice cakes ("tteok" in Korean).[197]

Rabbits have also appeared in religious symbolism. Buddhism, Christianity, and Judaism have associations with an ancient circular motif called the three rabbits (or "three hares"). Its meaning ranges from "peace and tranquility"[198] to the Holy Trinity.[199] The tripartite symbol also appears in heraldry.[200] In Jewish folklore, rabbits are associated with cowardice, a usage still current in contemporary Israeli spoken Hebrew. The original Hebrew word (shfanim, שפנים) refers to the hyrax, but early translations to English interpreted the word to mean "rabbit", as no hyraxes were known to northern Europe.[201]

-

Rabbit fools Elephant by showing the reflection of the moon. Illustration (from 1354) of the Panchatantra

-

Saint Jerome in the Desert, by Taddeo Crivelli (died about 1479)

Modern times

The rabbit as trickster is a part of American popular culture, as Br'er Rabbit (from African-American folktales[202] and, later, Disney animation[203]) and Bugs Bunny (the cartoon character from Warner Bros.[204]), for example.

Anthropomorphized rabbits have appeared in film and literature, in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (the White Rabbit and the March Hare characters), in Watership Down (including the film and television adaptations), in Rabbit Hill (by Robert Lawson), and in the Peter Rabbit stories (by Beatrix Potter). In the 1920s, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit was a popular cartoon character.[205]

On the Isle of Portland in Dorset, UK, the rabbit is said to be unlucky, and speaking the creature's name can cause upset among older island residents. This is thought to date back to early times in the local quarrying industry, where, to save space, extracted stones that were not fit for sale were set aside in what became tall, unstable walls. The local rabbits' tendency to burrow there would weaken the walls, and their collapse would result in injuries or even death. In the local culture to this day, the rabbit (when he has to be referred to) may instead be called a "long ears" or "underground mutton" so as not to risk bringing a downfall upon oneself.[206]

In other parts of Britain and in North America, "Rabbit rabbit rabbit" is one variant of an apotropaic or talismanic superstition that involves saying or repeating the word "rabbit" (or "rabbits" or "white rabbits" or some combination thereof) out loud upon waking on the first day of each month, because doing so is believed to ensure good fortune for the duration of that month.[207]

The "rabbit test" is a term first used in 1949 for the Friedman test, an early diagnostic tool for detecting a pregnancy in humans. It is a common misconception (or perhaps an urban legend) that the test-rabbit would die if the woman was pregnant. This led to the phrase "the rabbit died" becoming a euphemism for a positive pregnancy test.[208]

Many modern children's stories and cartoons portray rabbits as particularly fond of eating carrots. This is a misleading as wild rabbits do not naturally prefer carrots over other plants. Carrots are high in sugar, and excessive consumption can be unhealthy.[209] This has led to some owners of domestic rabbits feeding a carrot heavy diet on this false perception.[210][211]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ This genus is a hare, not a rabbit.

- ^ In addition to the common tapeti, several other species in genus Sylvilagus are known to inhabit South and Central America: the Andean tapeti, the Central American tapeti, the coastal tapeti, the Santa Marta tapeti, and the Venezuelan lowland rabbit.

Citations

- ^ a b Harper, Douglas. "rabbit". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ a b Harper, Douglas. "coney". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ Zapletal, D.; Švancarová, D.; Gálik, B. (2021). "Growth of suckled rabbit kits depending on litter size at birth". Acta Fytotechnica et Zootechnica. 24 (1): 55–59. doi:10.15414/afz.2021.24.01.55-59. ISSN 1335-258X.

- ^ Booth, J.L.; Peng, X.; Baccon, J.; Cooper, T.K. (2013). "Multiple complex congenital malformations in a rabbit kit (Oryctolagus cuniculi)". Comparative Medicine. 63 (4): 342–347. PMC 3750670. PMID 24209970.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "bunny". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Ballester, X.; Quinn, R. (2002). "Cuniculus 'Rabbit' — A Celtic Etymology" (PDF). World Rabbit Science. 10 (3).

- ^ Lipton, James (1 November 1993). An Exaltation of Larks: The Ultimate Edition. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-140-17096-0.

- ^ a b "Common Questions: What Do You Call a Group of...?". archived copy of Animal Congregations, or What Do You Call a Group of.....?. U.S. Geological Survey Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ "Warren Definition & Meaning". Britannica Dictionary. 2024. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ McClure, Diane (August 2020). "Breeding and Reproduction of Rabbits". Merck Veterinary Manual. Archived from the original on 2 October 2024. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ "Buck". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. 2023. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ "Doe". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Korth, William W. (1994), "Classification of Rodents", The Tertiary Record of Rodents in North America, Topics in Geobiology, vol. 12, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 27–34, doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-1444-6_4, ISBN 978-1-4899-1444-6, retrieved 16 September 2024

- ^ Asher RJ, Meng J, Wible JR, et al. (February 2005). "Stem Lagomorpha and the antiquity of Glires". Science. 307 (5712): 1091–4. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1091A. doi:10.1126/science.1107808. PMID 15718468. S2CID 42090505.

- ^

- Madsen O, Scally M, Douady CJ, et al. (February 2001). "Parallel adaptive radiations in two major clades of placental mammals". Nature. 409 (6820): 610–4. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..610M. doi:10.1038/35054544. PMID 11214318. S2CID 4398233.

- Murphy WJ, Eizirik E, Johnson WE, Zhang YP, Ryder OA, O'Brien SJ (February 2001). "Molecular phylogenetics and the origins of placental mammals". Nature. 409 (6820): 614–8. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..614M. doi:10.1038/35054550. PMID 11214319. S2CID 4373847.

- ^ a b Kriegs, JO; Churakov, G; Jurka, J; Brosius, J; Schmitz, J (April 2007). "Evolutionary history of 7SL RNA-derived SINEs in Supraprimates". Trends in Genetics. 23 (4): 158–61. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2007.02.002. PMID 17307271.

- ^ Huchon, Dorothée; Madsen, Ole; Sibbald, Mark J. J. B.; Ament, Kai; Stanhope, Michael J.; Catzeflis, François; de Jong, Wilfried W.; Douzery, Emmanuel J. P. (1 July 2002). "Rodent Phylogeny and a Timescale for the Evolution of Glires: Evidence from an Extensive Taxon Sampling Using Three Nuclear Genes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 19 (7): 1053–1065. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004164. ISSN 1537-1719. PMID 12082125.

- ^ Matthee, Conrad A.; et al. (2004). "A Molecular Supermatrix of the Rabbits and Hares (Leporidae) Allows for the Identification of Five Intercontinental Exchanges During the Miocene". Systematic Biology. 53 (3): 433–477. doi:10.1080/10635150490445715. PMID 15503672.

- ^ Hoffman, R.S.; Smith, A.T. (2005). "Order Lagomorpha". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 194–211. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c Alves, Ferrand & Hackländer 2008, pp. 1–9.

- ^ Varga 2013, p. 3.

- ^ Nowak 1999, p. 1720.

- ^ a b Nowak 1999, pp. 1733–1738.

- ^ a b Angerbjörn & Schai-Braun 2023, pp. 205–206.

- ^ a b Scandura, Massimo; De Marinis, Anna Maria; Canu, Antonio (2023), Hackländer, Klaus; Alves, Paulo C. (eds.), "Cape Hare Lepus capensis Linnaeus, 1758", Primates and Lagomorpha, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 79–98, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-34043-8_10, ISBN 978-3-030-34042-1, retrieved 16 September 2024

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bell, Diana; Smith, Andrew T. (2006), "Rabbits and Hares", The Encyclopedia of Mammals, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199206087.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-920608-7, retrieved 9 October 2024

- ^ Rodríguez-Martínez, Luisa; Hudson, Robyn; Martínez-Gómez, Margarita; Bautista, Amando (January 2014). "Description of the nursery burrow of the Mexican cottontail rabbit Sylvilagus cunicularius under seminatural conditions". Acta Theriologica. 59 (1): 193–201. doi:10.1007/s13364-012-0125-6. ISSN 0001-7051.

- ^ Delibes-Mateos et al. 2023, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Varga 2013, pp. 3–4.

- ^ "Desert Cottontail (Sylvilagus audubonii)". Texas Parks & Wildlife. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017.

- ^ Chapman, Joseph (1990). Rabbits, hares, and pikas : status survey and conservation action plan. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. p. 99. ISBN 2-8317-0019-1.

- ^ Alves, Ferrand & Hackländer 2008, pp. 241–249.

- ^ Angerbjörn & Schai-Braun 2023, pp. 119–219.

- ^ Lyon, M. W. (1916). "Belgian Hare, A Misleading Misnomer". Science. 43 (1115): 686–687. doi:10.1126/science.43.1115.686.b. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 1639908. PMID 17831801.

- ^ Whitman, Bob D. (October 2004). Domestic Rabbits & Their Histories: Breeds of the World. Leawood, KS: Leathers Publishing. pp. 74–95. ISBN 978-1-58597-275-3.

- ^ a b Toddes, Barbara (2022), Vonk, Jennifer; Shackelford, Todd K. (eds.), "Lagomorpha Diet", Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 3823–3826, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55065-7_1209, ISBN 978-3-319-55064-0, retrieved 13 November 2024

- ^ Irving-Pease, Evan K.; Frantz, Laurent A.F.; Sykes, Naomi; Callou, Cécile; Larson, Greger (2018). "Rabbits and the Specious Origins of Domestication". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 33 (3): 149–152. Bibcode:2018TEcoE..33..149I. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2017.12.009. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 29454669. S2CID 3380288.

- ^ Mapara, M.; Thomas, B.; Bhat, K. (2012). "Rabbit as an animal model for experimental research". Dental Research Journal. 9 (1): 111–8. doi:10.4103/1735-3327.92960 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMC 3283968. PMID 22363373.

Amongst various strains, New Zealand white strains of rabbits are commonly being used for research activities. These strains are less aggressive in nature and have less health problems as compared with other breeds.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Julie Kimber; Phillip Deery; Warwick Eather; Drew Cottle; Michael Hamel-Green; Nic Maclelland; Doris LeRoy; Jeanette Debney-Joyce; Jonathan Strauss; David Faber (2014). Issues on War and Peace. Australian Society for the Study of Labour History/Leftbank Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-9803883-3-6.

- ^ Marco Cullere; Antonella Dalle Zotte (2018). "Rabbit meat production and consumption: State of knowledge and future perspectives". Meat Science. 143: 137–146. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.04.029. PMID 29751220.

- ^ "Meat Production", Rabbit Production (10 ed.), GB: CABI, pp. 274–277, 11 May 2022, doi:10.1079/9781789249811.0023, ISBN 978-1-78924-978-1, retrieved 23 May 2024

- ^ Tislerics, Ati. "Oryctolagus cuniculus". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Fiorello, Christine V.; German, R.Z. (February 1997). "Heterochrony within species: craniofacial growth in giant, standard, and dwarf rabbits". Evolution. 51 (1): 250–261. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb02406.x. PMID 28568789. S2CID 205780205.

- ^ a b "Rabbit Breeds", Rabbit Production (10 ed.), GB: CABI, pp. 23–28, 11 May 2022, doi:10.1079/9781789249811.0003, ISBN 978-1-78924-978-1, archived from the original on 14 May 2024, retrieved 14 May 2024

- ^ Davis, Susan (2003). Stories Rabbits Tell. Lantern Books. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-59056-044-0.

- ^ Campbell, Darlene (1995). Proper Care of Rabbits. TFH Publications, Incorporated. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-86622-196-2.

- ^ a b Samson, Leslie (11 May 2022), "Angora Wool Production", Rabbit Production (10 ed.), GB: CABI, pp. 292–302, doi:10.1079/9781789249811.0022, ISBN 978-1-78924-978-1, retrieved 26 May 2024

- ^ Asher, RJ; Meng, J; Wible, JR; McKenna, MC; Rougier, GW; Dashzeveg, D; Novacek, MJ (18 February 2005). "Stem Lagomorpha and the antiquity of Glires". Science. 307 (5712): 1091–4. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1091A. doi:10.1126/science.1107808. PMID 15718468.

- ^ Johnson-Delaney, CA; Orosz, SE (May 2011). "Rabbit respiratory system: clinical anatomy, physiology and disease". Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 14 (2): 257–66. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2011.03.002. PMID 21601814.

- ^ a b c d Donnelly, Thomas M.; Vella, David (2020). "Basic Anatomy, Physiology, and Husbandry of Rabbits". In Quesenberry, Katherine; Orcutt, Connie J.; Mans, Christoph; Carpenter, James W. (eds.). Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery (4th ed.). pp. 131–149. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-48435-0.00011-3. ISBN 978-0-323-48435-0.

- ^ Hall, Patrick; Stubbs, Caleb; Anderson, David E.; Greenacre, Cheryl; Crouch, Dustin L. (17 June 2022). "Rabbit hindlimb kinematics and ground contact kinetics during the stance phase of gait". PeerJ. 10: e13611. doi:10.7717/peerj.13611. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 9208372. PMID 35734635.

- ^ d'Ovidio, Dario; Pierantoni, Ludovica; Noviello, Emilio; Pirrone, Federica (September 2016). "Sex differences in human-directed social behavior in pet rabbits". Journal of Veterinary Behavior. 15: 37–42. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2016.08.072.

- ^ van Praag, Esther (2005). "Deformed claws in a rabbit, after traumatic fractures" (PDF). MediRabbit.

- ^ a b "rabbit". Encyclopædia Britannica (Standard ed.). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2007.

- ^ Peiffer, Robert L.; Pohm-Thorsen, Laurie; Corcoran, Kelly (1994), "Models in Ophthalmology and Vision Research", The Biology of the Laboratory Rabbit, Elsevier: 409–433, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-469235-0.50025-7, ISBN 978-0-12-469235-0, PMC 7149682

- ^ Bensley, Benjamin Arthur (1910). Practical anatomy of the rabbit. The University Press. p. 1.

rabbit skeletal anatomy.

- ^ "Description and Physical Characteristics of Rabbits – All Other Pets – Merck Veterinary Manual". Merck Veterinary Manual. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ D.A.B.V.P., Margaret A. Wissman, D.V.M. "Rabbit Anatomy". exoticpetvet.net. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lumpkin, Susan; Seidensticker, John (2011). Rabbits: the animal answer guide. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0126-3. OCLC 794700391.

- ^ a b Khan, Madiha; Suh, Angela; Lee, Jenny; Granatosky, Michael C. (2021), "Lagomorpha Locomotion", in Vonk, Jennifer; Shackelford, Todd (eds.), Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–6, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_1199-1, ISBN 978-3-319-47829-6, retrieved 8 October 2024

- ^ Geiser, Max; Trueta, Joseph (May 1958). "Muscle action, bone rarefaction and bone formation". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 40-B (2): 282–311. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.40B2.282. PMID 13539115.

- ^ Lieber, Richard L.; Blevins, Field T. (January 1989). "Skeletal muscle architecture of the rabbit hindlimb: Functional implications of muscle design". Journal of Morphology. 199 (1): 93–101. doi:10.1002/jmor.1051990108. PMID 2921772. S2CID 25344889.

- ^ Varga 2013, p. 62.

- ^ Bertolino, Sandro; Brown, David E.; Cerri, Jacopo; Koprowski, John L. (2023), Hackländer, Klaus; Alves, Paulo C. (eds.), "Eastern Cottontail Sylvilagus floridanus (J. A. Allen, 1890)", Primates and Lagomorpha, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 67–78, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-34043-8_14, ISBN 978-3-030-34042-1, retrieved 16 September 2024

- ^ Allen, Joel Asaph (1877). "The influence of Physical conditions in the genesis of species". Radical Review. 1: 108–140.

- ^ Stevenson, Robert D. (1986). "Allen's Rule in North American Rabbits (Sylvilagus) and Hares (Lepus) Is an Exception, Not a Rule". Journal of Mammalogy. 67 (2): 312–316. doi:10.2307/1380884. ISSN 0022-2372. JSTOR 1380884.

- ^ "Black-tailed Jackrabbit - Lepus californicus". Montana Field Guide. Montana Natural Heritage Program and Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ a b Kluger, Matthew J.; Gonzalez, Richard R.; Mitchell, John W.; Hardy, James D. (1 August 1971). "The rabbit ear as a temperature sensor". Life Sciences. 10 (15): 895–899. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(71)90161-5. PMID 5566134.

- ^ Meyer, D. L. (1971). "Single Unit Responses of Rabbit Ear-Muscles to Postural and Accelerative Stimulation". Experimental Brain Research. 14 (2): 118–26. doi:10.1007/BF00234795. PMID 5016586. S2CID 6466476.

- ^ Capello, Vittorio (2006). "Lateral Ear Canal Resection and Ablation in Pet Rabbits" (PDF). The North American Veterinary Conference. 20: 1711–1713.

- ^ a b c Parsons, Paige K. (2018). "Rabbit Ears: A Structural Look: ...injury or disease, can send your rabbit into a spin". House Rabbit Society.

- ^ Hinds, David S. (31 August 1973). "Acclimatization of Thermoregulation in the Desert Cottontail, Sylvilagus audubonii". Journal of Mammalogy. 54 (3): 708–728. doi:10.2307/1378969. JSTOR 1378969. PMID 4744934.

- ^ Fayez, I; Marai, M; Alnaimy, A; Habeeb, M (1994). "Thermoregulation in rabbits". In Baselga, M; Marai, I.F.M. (eds.). Rabbit production in hot climates. Zaragoza: CIHEAM. pp. 33–41.

- ^ Varga 2013, p. 12.

- ^ Oladimeji, Abioja Monsuru; Johnson, Temitope Gloria; Metwally, Khaled; Farghly, Mohamed; Mahrose, Khalid Mohamed (January 2022). "Environmental heat stress in rabbits: implications and ameliorations". International Journal of Biometeorology. 66 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s00484-021-02191-0. ISSN 0020-7128. PMID 34518931.

- ^ Milling, Charlotte R; Rachlow, Janet L; Johnson, Timothy R; Forbey, Jennifer S; Shipley, Lisa A (1 September 2017). "Seasonal variation in behavioral thermoregulation and predator avoidance in a small mammal". Behavioral Ecology. 28 (5): 1236–1247. doi:10.1093/beheco/arx084. ISSN 1045-2249.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson-Delaney, Cathy A.; Orosz, Susan E. (2011). "Rabbit Respiratory System: Clinical Anatomy, Physiology and Disease". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice. 14 (2): 257–266. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2011.03.002. PMID 21601814.

- ^ a b Smith & Schenk 2019, p. 73.

- ^ a b Smith & Schenk 2019, p. 76.

- ^ a b c Jekl, Vladimi (2012). "Approach to Rabbit Respiratory Disease". WSAVA/FECAVA/BSAVA World Congress.

As obligate nasal breathers, rabbits with upper airway disease will attempt to breathe through their mouths, which prevents feeding and drinking and could be quickly fatal.

- ^ a b Autifi, Mohamed Abdul Haye; El-Banna, Ahmed Kamal; Ebaid, Ashraf El- Sayed (2015). "Morphological Study of Rabbit Lung, Bronchial Tree, and Pulmonary Vessels Using Corrosion Cast Technique". Al-Azhar Assiut Medical Journal. 13 (3): 41–51.

- ^ a b Varga 2013, pp. 13–33.

- ^ Smith, Susan M. (2020). "Gastrointestinal Physiology and Nutrition of Rabbits". In Quesenberry, Katherine; Orcutt, Connie J.; Mans, Christoph; Carpenter, James W. (eds.). Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery (4th ed.). pp. 162–173. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-48435-0.00013-7. ISBN 978-0-323-48435-0.

- ^ Bernard E. Rollin (13 March 1995). The Experimental Animal in Biomedical Research: Care, Husbandry, and Well-Being-An Overview by Species, Volume 2. CRC Press. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-8493-4982-9.

- ^ Karr-Lilienthal, Phd (University of Nebraska – Lincoln), Lisa (4 November 2011). "The Digestive System of the Rabbit". eXtension (a Part of the Cooperative Extension Service). Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ "Living with a House Rabbit". Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d Foote, Robert H; Carney, Edward W (2000). "The rabbit as a model for reproductive and developmental toxicity studies". Reproductive Toxicology. 14 (6): 477–493. Bibcode:2000RepTx..14..477F. doi:10.1016/s0890-6238(00)00101-5. ISSN 0890-6238. PMID 11099874.

- ^ a b c d e Pollock, C. (5 May 2014). "Rabbit Reproduction Basics". LafeberVet. Retrieved 18 September 2024.

- ^ Holtz, W.; Foote, R. H. (1 March 1978). "Composition of Rabbit Semen and the Origin of Several Constituents". Biology of Reproduction. 18 (2): 286–292. doi:10.1095/biolreprod18.2.286. ISSN 0006-3363. PMID 630026.

- ^ Foote, Robert H.; Hare, Elizabeth (10 September 2000). "High Catalase Content of Rabbit Semen Appears to be Inherited". Journal of Andrology. 21 (5): 664–668. doi:10.1002/j.1939-4640.2000.tb02134.x. ISSN 0196-3635. PMID 10975413.

- ^ Weisbroth, Steven H.; Flatt, Ronald E.; Kraus, Alan L. (1974). The Biology of the Laboratory Rabbit. doi:10.1016/c2013-0-11681-9. ISBN 978-0-12-742150-6.

- ^ Lukefahr, Steven D.; McNitt, James I.; Cheeke, Peter R.; Patton, Nephi M. (29 April 2022). Rabbit Production, 10th Edition. CABI. ISBN 978-1-78924-978-1.

- ^ a b Nowak 1999, p. 1730.

- ^ "Understanding the Mating Process for Breeding Rabbits". florida4h.org. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ Nowak 1999, pp. 1720–1732.

- ^ Benedek, I; Altbӓcker, V; Molnár, T (2021). "Stress reactivity near birth affects nest building timing and offspring number and survival in the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus)". PLOS ONE. 16 (1): e0246258. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1646258B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246258. PMC 7845978. PMID 33513198.

- ^ Varga 2013, pp. 34–38.

- ^ Jilge, B (1991). "The rabbit: a diurnal or a nocturnal animal?". Journal of Experimental Animal Science. 34 (5–6): 170–183. PMID 1814463.

- ^ Holland, Jennifer S. (July 2011). "40 Winks?". National Geographic. 220 (1).

- ^ Pivik, R.T.; Bylsma, F.W.; Cooper, P. (May 1986). "Sleep—wakefulness rhythms in the rabbit". Behavioral and Neural Biology. 45 (3): 275–286. doi:10.1016/S0163-1047(86)80016-4. PMID 3718392.

- ^ Aguilar-Roblero, R; González-Mariscal, G. (2020). "Behavioral, neuroendocrine and physiological indicators of the circadian biology of male and female rabbits". Eur J Neurosci. 51 (1): 429–453. doi:10.1111/ejn.14265. PMID 30408249.

- ^ Varga 2013, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Parsons, Paige K. "The Rabbit Eye: A Complete Guide". Rabbit.Org Foundation. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ a b Davidson, Alan (2014). Jaine, Tom (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 1899–1901. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199677337.001.0001. ISBN 9780191756276.

- ^ Cooke, Brian Douglas (2014). Australia's War Against Rabbits. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-09612-7. Archived from the original on 7 June 2014.

- ^

- Meredith, A (2013). "Viral skin diseases of the rabbit". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice. 16 (3): 705–714. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2013.05.010. PMID 24018033.

- Kerr, P (2017). "Genomic and phenotypic characterization of myxoma virus from Great Britain reveals multiple evolutionary pathways distinct from those in Australia". PLOS Pathogens. 13 (3): e1006252. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1006252. PMC 5349684. PMID 28253375.

- ^ Latney, La'Toya (2014). "Encephalitozoon cuniculi in pet rabbits: diagnosis and optimal management". Veterinary Medicine: Research and Reports. 5: 169–180. doi:10.2147/VMRR.S49842. PMC 7337189. PMID 32670857.

- ^ Wood, Maggie. "Parasites of Rabbits". Chicago Exotics, PC. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ Boschert, Ken. "Internal Parasites of Rabbits". Net Vet. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ Krempels, Dana. "GastroIntestinal Stasis, The Silent Killer". Department of Biology at the University of Miami. Archived from the original on 19 June 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "Rabies: Other Wild Animals". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 November 2011. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Rabbit hemorrhagic disease". American Veterinary Medical Association. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ Abrantes, Joana; van der Loo, Wessel; Le Pendu, Jacques; Esteves, Pedro J. (10 February 2012). "Rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD) and rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV): a review". Veterinary Research. 43 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/1297-9716-43-12. ISSN 1297-9716. PMC 3331820. PMID 22325049.

- ^ Bárcena, Juan; Guerra, Beatriz; Angulo, Iván; González, Julia; Valcárcel, Félix; Mata, Carlos P.; Castón, José R.; Blanco, Esther; Alejo, Alí (24 September 2015). "Comparative analysis of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) and new RHDV2 virus antigenicity, using specific virus-like particles". Veterinary Research. 46 (1): 106. doi:10.1186/s13567-015-0245-5. ISSN 1297-9716. PMC 4581117. PMID 26403184.

- ^ Ambagala, Aruna; Schwantje, Helen; Laurendeau, Sonja; Snyman, Heindrich; Joseph, Tomy; Pickering, Bradley; Hooper-McGrevy, Kathleen; Babiuk, Shawn; Moffat, Estella; Lamboo, Lindsey; Lung, Oliver; Goolia, Melissa; Pinette, Mathieu; Embury-Hyatt, Carissa (July 2021). "Incursions of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus 2 in Canada—Clinical, molecular and epidemiological investigation". Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 68 (4): 1711–1720. doi:10.1111/tbed.14128. ISSN 1865-1674. PMID 33915034.

- ^ Ramsey, David S.; Patel, Kandarp K.; Campbell, Susan; Hall, Robyn N.; Taggart, Patrick L.; Strive, Tanja (12 May 2023). "Sustained Impact of RHDV2 on Wild Rabbit Populations across Australia Eight Years after Its Initial Detection". Viruses. 15 (5): 1159. doi:10.3390/v15051159. ISSN 1999-4915. PMC 10223972. PMID 37243245.

- ^ "Deadly rabbit disease confirmed in Thurston County; vets urge vaccination". Washington State Department of Agriculture. 25 September 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ Fedriani, J. M.; Palomares, F.; Delibes, M. (1999). "Niche relations among three sympatric Mediterranean carnivores" (PDF). Oecologia. 121 (1): 138–148. Bibcode:1999Oecol.121..138F. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.587.7215. doi:10.1007/s004420050915. JSTOR 4222449. PMID 28307883. S2CID 39202154. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Tynes, Valarie V. (2010). Behavior of Exotic Pets. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 70–73. ISBN 978-0-8138-0078-3. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016.

- ^ Bringmann, Andreas; Syrbe, Steffen; Görner, Katja; Kacza, Johannes; Francke, Mike; Wiedemann, Peter; Reichenbach, Andreas (1 September 2018). "The primate fovea: Structure, function and development". Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 66: 49–84. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.03.006. ISSN 1350-9462. PMID 29609042.

- ^ Lavaud, Arnold; Soukup, Petr; Martin, Louise; Hartnack, Sonja; Pot, Simon (23 April 2020). "Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography in Awake Rabbits Allows Identification of the Visual Streak, a Comparison with Histology". Translational Vision Science & Technology. 9 (5): 13. doi:10.1167/tvst.9.5.13. ISSN 2164-2591. PMC 7401941. PMID 32821485.

- ^ a b Varga 2013, p. 3-4.

- ^ Davis, Susan E.; DeMello, Margo (2003). Stories Rabbits Tell: A Natural And Cultural History of A Misunderstood Creature. Lantern Books. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-59056-044-0. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016.

- ^ Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness World Records 2014. Guinness World Records Limited. pp. 043. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- ^ "Cottontail rabbit". Indiana Department of Natural Resources. 29 January 2021. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024.

- ^ Carey, James R.; Judge, Debra S. (2000). Longevity Records. Monographs on Population Aging. Vol. 8. Odense University Press. ISBN 87-7838-539-3. ISSN 0909-119X.

- ^ "AnAge entry for Brachylagus idahoensis". AnAge: The Animal Ageing and Longevity Database. Human Ageing Genomic Resources. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Weigl, Richard (2005). Longevity of Mammals in Captivity; from the Living Collections of the World. Stuttgart: Kleine Senckenberg-Reihe 48.

- ^ "AnAge entry for Oryctolagus cuniculus". AnAge: The Animal Ageing and Longevity Database. Human Ageing Genomic Resources. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Péron, Guillaume; Lemaître, Jean-François; Ronget, Victor; Tidière, Morgane; Gaillard, Jean-Michel (13 September 2019). "Variation in actuarial senescence does not reflect life span variation across mammals". PLoS Biol. 17 (9): e3000432. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000432. PMC 6760812. PMID 31518381.

- ^ Ge, Deyan; Wen, Zhixin; Xia, Lin; Zhang, Zhaoqun; Erbajeva, Margarita; Huang, Chengming; Yang, Qisen (3 April 2013). Evans, Alistair Robert (ed.). "Evolutionary History of Lagomorphs in Response to Global Environmental Change". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e59668. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...859668G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059668. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3616043. PMID 23573205.

- ^ Sylvilagus aquaticus (swamp rabbit) Archived 2013-05-27 at the Wayback Machine, Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

- ^ Caravaggi, Anthony (2022), Vonk, Jennifer; Shackelford, Todd K. (eds.), "Lagomorpha Life History", Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 3826–3834, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55065-7_1206, ISBN 978-3-319-55064-0, retrieved 13 November 2024

- ^ Southern, H. N. (November 1940). "The ecology and population dynamics of the wild rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus)". Annals of Applied Biology. 27 (4): 509–526. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.1940.tb07522.x.

- ^ a b Marshall, Larry G.; Webb, S. David; Sepkoski, J. John; Raup, David M. (1982). "Mammalian Evolution and the Great American Interchange". Science. 215 (4538): 1351–1357. Bibcode:1982Sci...215.1351M. doi:10.1126/science.215.4538.1351. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 1688046. PMID 17753000.

- ^ a b Long, J.-R.; Qiu, X.-P.; Zeng, F.-T.; Tang, L.-M.; Zhang, Y.-P. (April 2003). "Origin of rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in China: evidence from mitochondrial DNA control region sequence analysis". Animal Genetics. 34 (2): 82–87. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2052.2003.00945.x. ISSN 0268-9146. PMID 12648090.

- ^ Emmons, Louise H.; Feer, Francois (1990). Neotropical Rainforest Mammals: A Field Guide. University of Chicago Press. pp. 227–228.

- ^ Cassini, Marcelo H.; Rivas, Luciano (August 2023). "Lack of evidence of significant impact of European rabbits on Patagonian forest regeneration". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 69 (4): 74. Bibcode:2023EJWR...69...74C. doi:10.1007/s10344-023-01710-1. ISSN 1612-4642.

- ^ Beischer, DE; Fregly, AR (1962). "Animals and man in space. A chronology and annotated bibliography through the year 1960". US Naval School of Aviation Medicine. ONR TR ACR-64 (AD0272581). Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ Hoffman, Kurt L.; Hernández Decasa, D. M.; Beyer Ruiz, M. E.; González-Mariscal, Gabriela (5 March 2010). "Scent marking by the male domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) is stimulated by an object's novelty and its specific visual or tactile characteristics". Behavioural Brain Research. 207 (2): 360–367. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2009.10.021. ISSN 0166-4328. PMID 19857527. S2CID 10827948.

- ^ "Scent glands". Rabbit Welfare Association & Fund (RWAF). Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ Arteaga, Lourdes; Bautista, Amando; Martínez-Gómez, Margarita; Nicolás, Leticia; Hudson, Robyn (June 2008). "Scent marking, dominance and serum testosterone levels in male domestic rabbits". Physiology & Behavior. 94 (3): 510–515. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.03.005. PMID 18436270.

- ^ Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development; Agriculture and Food Division; Pest and Disease Information Service (PaDIS). "Rabbit control: fumigation". agric.wa.gov.au. Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ Crawford, J S (1969). "History of the state vermin barrier fences, formerly known as rabbit proof fences". Research Reports. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Cowan, D. P. (1 December 1984). "The use of ferrets (Mustela furo) in the study and management of the European wild rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus)". Journal of Zoology. 204 (4): 570–574. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1984.tb02391.x. ISSN 1469-7998.

- ^ Williams, Kent; Parer, Ian; Coman, Brian; Burley, John; Braysher, Mike (1995). Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits. Canberra: Australian Govt. Pub. Service. ISBN 978-0644296236. OCLC 153977337.

- ^ Williams, Kent; Parer, Ian; Coman, Brian; Burley, John; Braysher, Mike (1995). Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits. Canberra: Australian Govt. Pub. Service. ISBN 978-0644296236. OCLC 153977337.

- ^ CSIRO. "Biological control of rabbits". www.csiro.au. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ Meredith, A (2013). "Viral skin diseases of the rabbit". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice. 16 (3): 705–714. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2013.05.010. PMID 24018033.

- ^ "Feral animals in Australia — Invasive species". Environment.gov.au. 1 February 2010. Archived from the original on 21 July 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Rabbits — The role of government — Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. 1 March 2009. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Jerez, Sara (23 February 2023). ""Es cierto": Experto confirma que conejos y otros animales en llamas sí pueden propagar incendios". Radio Bío-Bío (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ a b del Mar Parra, Maria (23 February 2023). "Experto forestal: "Los conejos no son un agente significativo de propagación de incendios"". El Desconcierto (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Seuru, S.; Perez, L.; Burke, A. (2023). "Why Were Rabbits Hunted in the Past? Insights from an Agent-Based Model of Human Diet Breadth in Iberia During the Last Glacial Maximum". In Seuru, S.; Albouy, B. (eds.). Modelling Human-Environment Interactions in and beyond Prehistoric Europe. Themes in Contemporary Archaeology. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-34336-0_7. ISBN 978-3-031-34335-3.

- ^ Bender, David A. (2003). "game". A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 2335. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199234875.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-923487-5.

- ^ Southam, Hazel (July 2012). "Natural Selection". Geographical. 84 (7). Geographical Magazine Ltd.: 40–43 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Linduska, J. P. (1947). "The Ferret as an Aid to Winter Rabbit Studies". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 11 (3): 252–255. doi:10.2307/3796283. ISSN 0022-541X. JSTOR 3796283.

- ^ a b McKean, Andrew (October 2008). "Fall's Forgotten Hunt". Outdoor Life. 215 (9): 58–62 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Nickens, T. Edward (June 2020). "Snare a Rabbit". Field & Stream. 125 (2): 53 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Room, Adrian (2010). Dictionary of Sports and Games Terminology. McFarland. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-7864-5757-1.

- ^ a b Olivia Geng, French Rabbit Heads: The Newest Delicacy in Chinese Cuisine Archived 14 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Wall Street Journal Blog, 13 June 2014

- ^ "FAOSTAT". FAO. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ FAO – The Rabbit – Husbandry, health and production. Archived 23 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alves, Joel M.; Carneiro, Miguel; Day, Jonathan P.; Welch, John J.; Duckworth, Janine A.; Cox, Tarnya E.; Letnic, Mike; Strive, Tanja; Ferrand, Nuno; Jiggins, Francis M. (30 August 2022). "A single introduction of wild rabbits triggered the biological invasion of Australia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 119 (35): e2122734119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11922734A. doi:10.1073/pnas.2122734119. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 9436340. PMID 35994668.

- ^ Alyse Edwards (20 April 2014). "Rabbit meat disappearing from consumers' tables as farmers struggle with spiralling costs". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Smith, Ed (4 October 2018). The Borough Market Cookbook: Recipes and stories from a year at the market. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4736-7869-9.

- ^ 'Traditional Moroccan Cooking, Recipes from Fez', by Madame Guinadeau. (Serif, London, 2003). ISBN 1-897959-43-5.

- ^ "Rabbit: From Farm to Table". USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service. 12 January 2006. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008.

- ^ a b "Seasonal Incidence of Tularaemia and Sources of Infection". Public Health Reports. 42 (48): 2948–2951. 1927. ISSN 0094-6214. JSTOR 4578598.

- ^ "Signs and Symptoms of Tularemia". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 May 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ "Tularemia (Rabbit fever)". Health.utah.gov. 16 June 2003. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Penn, R.L. (2014). Francisella tularensis (Tularemia) In J. E. Bennett, R. Dolin, & M. J. Blaser (Eds.), Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 2590–2602. ISBN 978-1-4557-4801-3.

- ^ Xian, Vivian (2007). "China, Where American Mink Gets Glamour". USDA Foreign Agricultural Service Global Agriculture Information Network. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Houdebine, Louis-Marie; Fan, Jianglin (1 June 2009). Rabbit Biotechnology: Rabbit Genomics, Transgenesis, Cloning and Models. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 68–72. ISBN 978-90-481-2226-4. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ Lebas, F.; Coudert, P.; Rouvier, R.; de Rochambeau, H. (1986). "Production of rabbit skins and angora wool". The rabbit husbandry, health and production. FAO Animal Production and Health. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ a b Stein, Sadie (31 March 2024). "Our Bunnies, Ourselves". The New York Times Book Review: 22 – via Gale General OneFile.

- ^ Windling, Terri (2005). "The Symbolism of Rabbits and Hares". Endicott Studio. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Harley, Marta Powell (1985). "Rosalind, the Hare, and the Hyena In Shakespeare's "As You Like It"". Shakespeare Quarterly. 36 (3): 335–337. doi:10.2307/2869713. ISSN 0037-3222. JSTOR 2869713.

- ^ Cross, Gary (13 May 2004). "Holidays and New Rituals of Innocence". The Cute and the Cool. Oxford University Press. pp. 83–120. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195156669.003.0004. ISBN 978-0-19-515666-9.

- ^ "Watership Downs". Masterplots II: Juvenile and Young Adult Fiction Series. Vol. 4: Sev–Z, Indexes. Salem Press, Inc. 1991.

- ^ Lanes, Selma G. (30 June 1974). "Male Chauvinist Rabbits". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ Swier, Patricia L. (2013). "REBELLIOUS RABBITS: CHILDHOOD TRAUMA AND THE EMERGENCE OF THE UNCANNY IN TWO SOUTHERN CONE TEXTS". Chasqui (in Spanish). 42 (1): 166–80 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Kelly, John (5 April 2016). "The Erotic Rabbits of Easter". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ Fowles, Jib (23 January 1996). Advertising and Popular Culture. SAGE. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-0-8039-5483-0.